Organizational Frontlines: What are they and why they matter?

Today’s broadband Internet and wireless technologies enable organization-customer interactions of ever-increasing diversity and consistency across multiple touch points. These touch-points are evolving as sites of vibrant innovations and interventions that engage customers, enhance customer experiences, and motivate value (co)creation.

Organizational frontlines (OF) is a study of touch-points.

Specifically, OF is defined as the study of interactions and interfaces at the point of contact between an organization and its customers that promote, facilitate, or enable value creation and exchange.

.png)

A 2x2 framework (see below) illustrates the distinct nature and dynamics of OF inquiry in the four quadrants that define the intersection between interfaces (lean to rich) and interactions (simple to complex). This framework uses five dimensions to develop OF inquiry:

(a) idea, a theoretical concept that is typical of a quadrant (b) focus, the outcomes that are typically of interest for a quadrant (c) fields, the diverse disciplines that typically study the ideas and focus of a quadrant (d) technology, the technical advances that are relevant for a quadrant (e) examples, typical practice applications relevant for a quadrant

.png)

Future research and practice in OF is likely to benefit from pursuing 3 key topics:

Time as a key Dimension – theorizing the role of time in understanding frontline interactions and interfaces in retailing.

- How can the varied conceptions of clock and event time be used to advance the study of patterns and predictions of customer interactions and interfaces?

- How might frontline theories be adapted to integrate clock and event time?

- Which conception(s) of time as a construct are likely to yield frontline insights , and why?

Beyond Dualities Dichotomies, such as human vs. machine or touch vs. tech, are useful to establish contrast and highlight distinctions, are proving too simplistic for understanding the nuanced and varied features that characterize today’s frontline interactions and interfaces.

- How to develop meaningful typologies and taxonomies to promote a systematic analysis of the exploding variety in technology deployment and devices that blend frontline human and machine functions?

- What are the role and influences of empathy and social constructs in a technology-infused world of B2B and B2C digital customer experiences?

- What combinations or configurations of human (touch) and machine (tech) functions are most effective for what interactions and by using what interfaces in customer journeys?

Logics of Ecosystems – ecosystems as an embedding system that institutionalizes logics to coordinate and innovate the interfaces and interactions for continuity and consistency in customer experiences.

- Why do some ecosystems that support frontline technologies function effectively, and why do others fail and falter?

- How and under what conditions are the logics of ecosystems adopted or resisted by frontline agents and customers?

- What are the contexts, phenomena, and advancements that impact and/or alter the frontline ecosystem for customer-centric firms?

Read more about this research Synergies at the Intersection of Retailing and Organizational Frontlines Research The Emergent Field of Organizational Frontlines

One Voice Strategy for Customer Engagement

For most of history, service exchanges involved face-to-face interactions between customers and firms. Technology shattered that constraint, and today there are more kinds of services delivered in more places, at more times, and at lower cost than ever before. This enabling technology is complex and changes quickly.

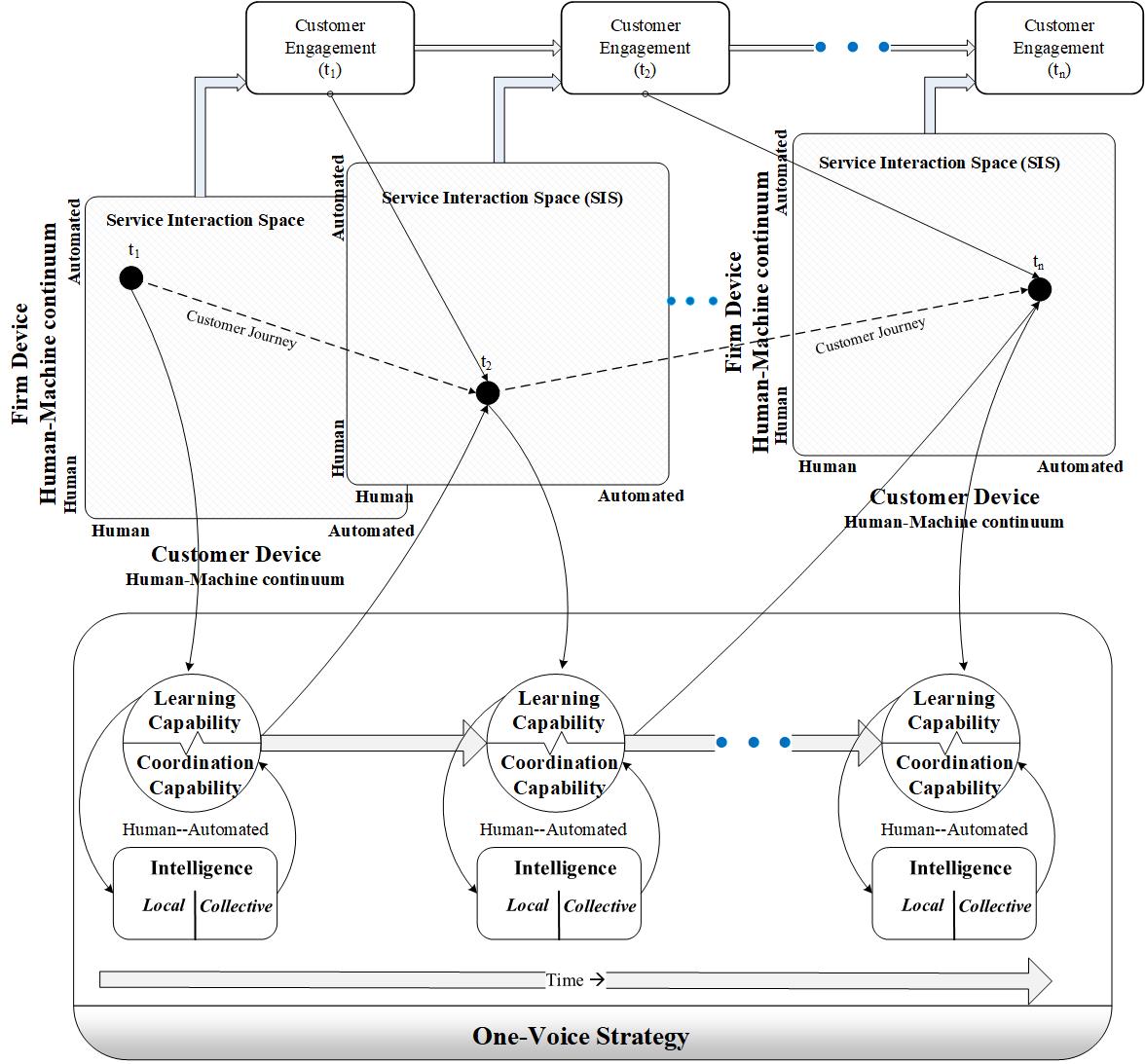

A firm’s challenge is to deliver a coherent stream of seamless, harmonious, and reliable experiences across customer journeys by developing, what we conceptualize, as a One-Voice Strategy to win customer engagement.

Our research shows that an effective one-voice strategy requires the integration of three factors:

- Interfaces that require interactions

- Learning capabilities that generate intelligence

- Coordination capabilities that use this intelligence to enhance subsequent interactions

Our research also shows that a firm's success at One-Voice Strategy comes from mobilizing practices and resources in their workplace to reflect three insights:

-

➣ Customer-firm interaction is the basic unit of analysis in winning customer engagement. Every interaction can be viewed as located in a Service Interaction Space (SIS)---a universe of possible, feasible and imaginable points of customer-firm interaction, where each point involves a specific interface that permits a firm and customer to connect over time and space using varying devices. Both the customer and the firm have a continuum of choices that runs from 100% human to 100% machine-mediated. Crossing these two continua creates the SIS.

- Where in the SIS should we compete?

- When should we invest in new interfaces, so that they are neither too soon nor too late to serve customers’ shifting preferences?

- How are we to manage the multitude of potential interactions created by different combinations of devices and interfaces?

- How should we make tradeoffs among the attributes, which are quality, speed, cost, agency (the customer’s sense of control), and social functionality (the capacity to detect or display emotions), to create desired customer experiences?

- What parts of the learning function can be automated with marketing technology (martech) software?

- What parts require human insights to identify subtle patterns or nuances?

- How can local intelligence be converted to collective intelligence without overburdening frontline employees with data management tasks?

- How is the matrixed firm to avoid silos that slow cross-functional decision making?

- How can they offset the effects of geographical dispersion and communication overhead that slows collaboration?

Thus, a One Voice Strategy enables a firm to integrate all the organization’s frontline and backend processes to deliver competitive interactions anytime, anywhere, and with any combination of human and machine devices. Liebig’s law of the minimum applies here: the weakest factor – interfaces, learning and coordination capabilities, or strategy – limits how well experiences can be delivered and hence the quality of customer engagement achieved.

Read more about this research.

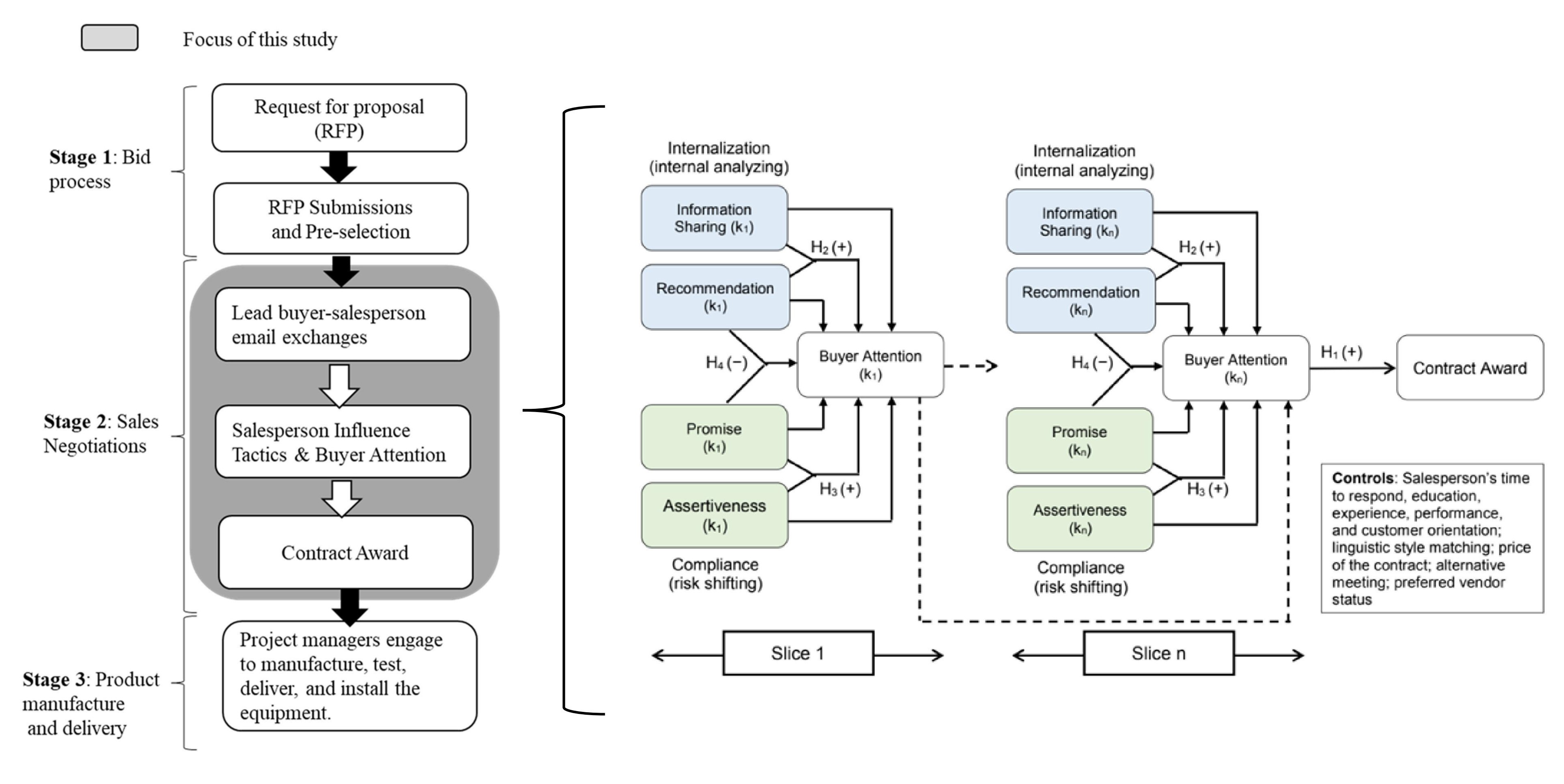

B2B E-Negotiations and Influence Tactics

How to manage e-communications and win contracts

According to reports, 77% customers prefer e-communications over other formats resulting in 75% increase in e-negotiations and, by one estimate, 80% of U.S. sales negotiations are conducted online. Yet, little is known about effectiveness of B2B e-negotiations.

- How salespeople use e-communications to influence buyers and win contracts?

- How do buyers process salespeople’s influence tactics during e-negotiations?

The first question addresses what works, and the second explains why it works.

Our research team worked with a B2B firm to collect data for more than 40 e-negotiations over a two year-period. We predicted the probability of wining multimillion dollar sales contract in competitive bid negotiations. We identified influence tactics expressed as textual cues, and used by salespeople in interactions with buyers during the e-negotiation sales process. Specifically, we identified four influence tactics:

• information sharing, sharing knowledge about solutions/services/products

• recommendation, explicit suggestion favoring a particular solution/service/product

• promise, committing to a future course of action, activity and/or benefit

• assertiveness, call-to-action for the buyer to ensure continuity of the exchange/relationship

What Works to Win Contracts--Findings

- No individual influence tactic is sufficient to hold a buyer’s attention and to win the contract award.

- A 30% increase in buyer attention increases the likelihood of a contract award by 7-fold.

- Effective use of influence tactics requires the concurrent use of complementary tactics.

- Concurrent use of assertiveness and promise tactics boost buyer attention by 14% on average. Assertiveness and promise are complementary tactics.

- Concurrent use of information sharing and recommendation tactics results in a 15% increase in buyer attention. Information-sharing and recommendation are complementary tactics.

- Concurrent use of recommendation and promise tactics results in a 30% decrease in buyer attention, and a 7-fold lower probability of contract award. Recommendation and Promise are competing tactics.

Why it works—Findings

While past research identifies what influence tactics are effective in different sales contexts, our study explains why influence tactics work.

- Waxing and waning of buyer attention in B2B sales negotiation, visible in the signals of buyer’s messaging, is an early indication of sales effectiveness and diagnostic of the likelihood of sales contract award.

- Buyer attention explains how buyers notice, process and respond to salesperson influence tactic in accord with attention’s role in a selection, resource-allocation and action-motivation mechanism, respectively.

- Information sharing and recommendation work to gain buyer attention by persuading the receiver to focus on the merit of the argument (internal-analyzing).

- Promise and assertiveness work to gain buyer attention by mitigating decision risk, simplifying information processing, and/or reducing uncertainty (risk-shifting).

Read more about this research.

How to Stem Knowledge Losses in Marketing Frontlines, and Enhance Customer Satisfaction, Efficiency and Revenue

Why are so few firms successful in delivering high quality in service interactions without unnecessarily increasing costs? Why do firms find it so hard to cut through productivity-quality trade-offs?

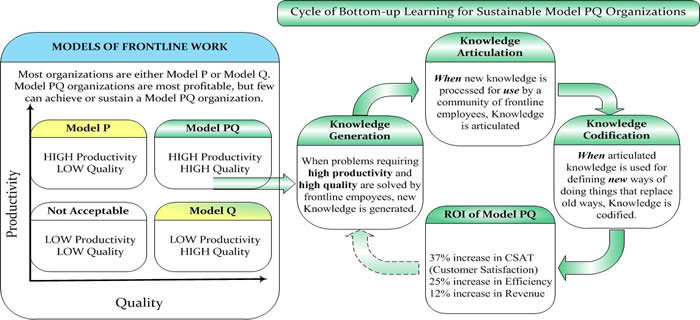

Productivity or quality is a perennial dilemma in modern organizations. Most organizations are either productivity focused by controlling costs (Model P) or quality focused by delivering excellent customer service (Model Q). Few organizations can achieve or sustain a dual focus that cuts through productivity-quality trade-offs (Model PQ). Empirical data consistently suggest that Model PQ organizations are most profitable and outcompete Model P and Model Q organizations in their category. Our research shows that business units that are successful in cutting through productivity-quality trade-offs have one thing in common: they are more effective in learning from the frontlines and in leveraging this bottom-up learning to innovate service processes.

We refer to our insight as the Cycle of Bottom-up Learning for Sustainable Model PQ Organizations (see Figure below).

Our results show that the cycle of bottom-up learning leads to a 37% gain in customer satisfaction, 25% increase in efficiency, and 15% higher revenue. The bottom-up learning cycle has three knowledge components that organizations need to cultivate and connect: Knowledge Generation, Articulation and Codification.

•Organizations cultivate new knowledge generation when frontline employees are empowered to break from the standard operating procedure to creatively construct or improvise PQ solutions that address unanticipated customer needs, requests or complaints.

• Knowledge generated in the frontlines is often lost because it is hard to capture and codify directly. To stem these losses, organizations cultivate knowledge articulation where frontline employees are connected in innovation councils to share, process, and distil generated knowledge to discover new ways of practice.

• All articulated knowledge is not useful in delivering PQ returns. Organizations make middle managers accountable for sifting, sorting, and synthesizing knowledge articulated by frontlines to codify useful knowledge as new operating practice.

Read more about this research.

Performance Losses in Service Innovation Implementation: A Frontline Perspective

Good ideas often fail at the altar of execution. A 2007 McKinsey Global Survey of “Innovation in Financial Services” shows that over 70% of senior executives agreed that innovation is critical for organizational success, yet half indicated that their organizations suffer from “performance gap” due to poor implementation that robs service innovations of bottom line payoffs.

What is the remedy to close the performance gaps?

The 2007 McKinsey Survey provides a clue: “When asked which practices, if implemented effectively, would promote successful innovation, executives make people-related [factors] their top priorities.” The Centre for Services Leadership at the Arizona State University concurs by noting that understanding when and why service innovations fail or succeed requires placing frontline employees “squarely within the theoretical domain of innovation implementation.”

Our study provides this understanding and offers insights for managers interested in stemming performance losses in service innovation implementation.

Our point-of-view is that understanding how frontline employees make sense of service innovations and how this sense making amplifies or abates their resistance to it is critical to detecting and understanding performance losses during implementation.

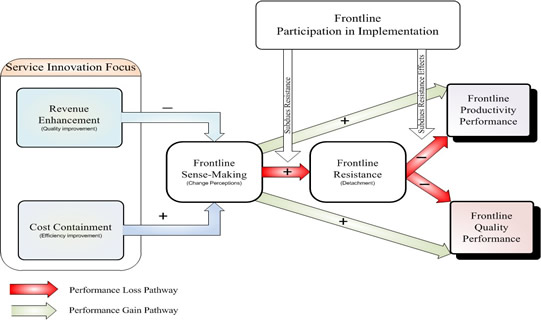

Our studies of frontlines in service organizations have uncovered three patterns in frontline sense-making and performance loss (see Figure below).

- When service innovations focus on revenue enhancement through quality improvement initiatives, frontline employees perceive the change as less disruptive; by contrast, service innovation focused on cost containment is perceived as more disruption to their role.

- Change and disruption of roles diminish performance by provoking frontline resistance. However, change in itself can be motivating and bolster performance. Thus, service innovation implementation generates both a performance loss pathway (red connections) and a performance gain pathway (green connections).

- When performance loss dominates, it drains away performance gains and service innovation implementation is ineffective. Frontline participation in innovation development and implementation can subdue both the degree to which frontlines resist change, and the negative effect of resistance to change.

For more details on how frontline participation mitigates performance losses, Click Here

Read more about this research.

New Rules for Effective Customer Problem Solving in Service Organizations: Fresh Insights from Big Data*

A 2017 study shows that 62 million families in the US are estimated to report at least 1 service problem/year with a median experienced loss of $250 leaving 56% customers in a “rage”—extremely upset—category. Only 25% of the customers were able to resolve the service problem in 1 company contact, and 19% reported requiring > 7 contacts to obtain resolution. 80% of the customers remained unhappy even after resolution efforts.Cost of ineffective problem solving is estimated at $313 billion in future sales (US data). Service organizations are especially vulnerable.

Why is it so hard, and what can service organizations do to get ahead?

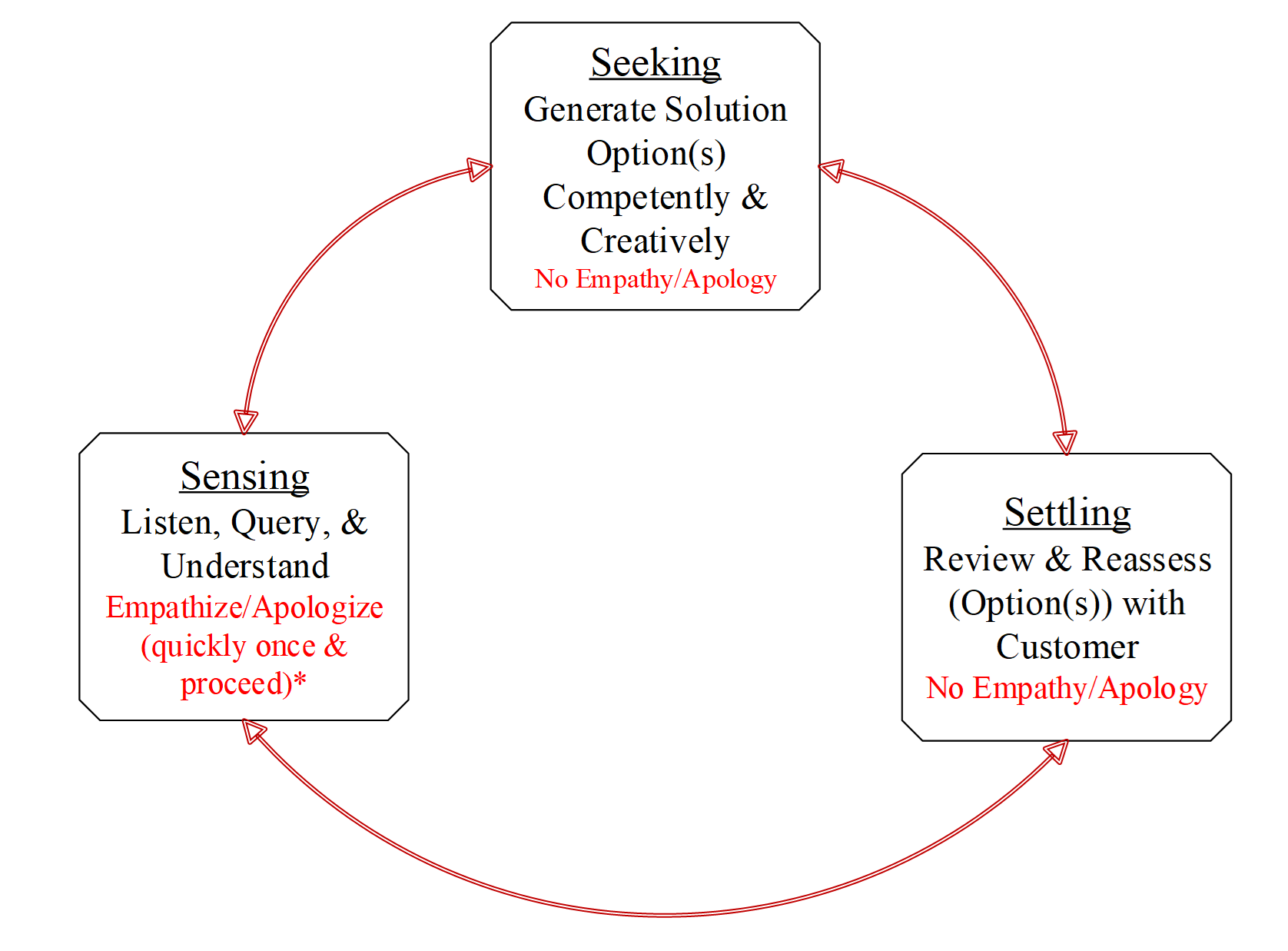

My research program using, for the first time, video recordings of customer problem solving interactions reveals fresh insights.* To understand these insights , it is useful to first map the anatomy of a customer problem solving interaction which involves three phases with distinct goals (see figure):

- Sensing—problem comprehension and communication

- Seeking—generating meaningful solution options

- Settling—negotiating and implementing an acceptable solution option

Frontline agents and customers freely go back and forth among these phases to achieve the three goals—to comprehend, to generate and to negotiate.These phases help in revealing new insights regarding customer problem solving in the context of airline travel (e.g., missed flight, lost baggage).

-

Emphasizing or apologizing (e.g., relational skills) is appropriate only in the “sensing” phase — 5 to 7 seconds are adequate — but must quickly transition to creative problem solving.

Rule 1: Keep empathizing/apologizing to the minimum. Say it once and move on.

Corollary 1: Listen to understand and comprehend the unique nature of customer problem.

-

Creative Solving skills—competence, ingenuity and improvisation to generate multiple solution options—are most valued by customers in the “seeking” and “settling” phases.

Rule 2: Focus on competent and creative generation of solution options that are meaningful and relevant (to the customer).

Corollary 2: Number of meaningfully different and directly relevant solution options generated matter.

-

Customers penalize frontline agents who engage in continued relational work during “seeking” and “settling” phases by discounting their perceived competence.

Rule 3: Repeatedly apologizing, empathizing or engaging in non-problem-solving topics raises customer concerns about focus on, and timely progress toward competent & creative problem solving.

Corollary 3: Talk to the customer about problem solving actions taken to affirm focus and attention.

-

Customers reward problem-solving competence when they can choose from several generated options because it gives them a sense of control over a difficult situation.

Rule 4: Concede control to customers in the “settling” phase so they can exercise a decision right to choose among different solution options.

Corollary 4: Avoid giving a false sense of decision choice by generating obviously poor (“nonsensical”) solution options.

*This research is highlighted in an article titled, “Sorry is Not Enough” in the January-February 2018 issue of the Harvard Business Review.

Read more about this research at The Conversation.

Read more about this research at HBR.

Listen to the podcast at NPR.

Cycle of Frontline Problem Solving for Effective Customer Recovery